Inside out approach to learn git

Git is one of the most common version control system used today. And the fact that it was developed by the kernel developers justifies that it is very complex and have a very bad interface. And most of the commands don’t make much of a sense at first.

But behind the scenes git uses a bunch of tricks in different combinations to make everything work. And once you understand them all the git commands start making much more sense than ever. For this we need to understand the git internals. (There is a lot to the git internals but we are just going to cover a few of them)

Understanding git internals

To understand this, we first need to create a git repository and start working on it. For that, I have created a simple folder play-git here to start playing around. This is usually referred as working area or working repository or working directory.

Next step after this will be creating/initializing a git repository. This can be done using git init command in the working directory.

[ OUTPUT ]:

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/ayedaemon/extra/playground/play-git/.git/

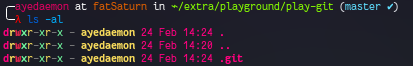

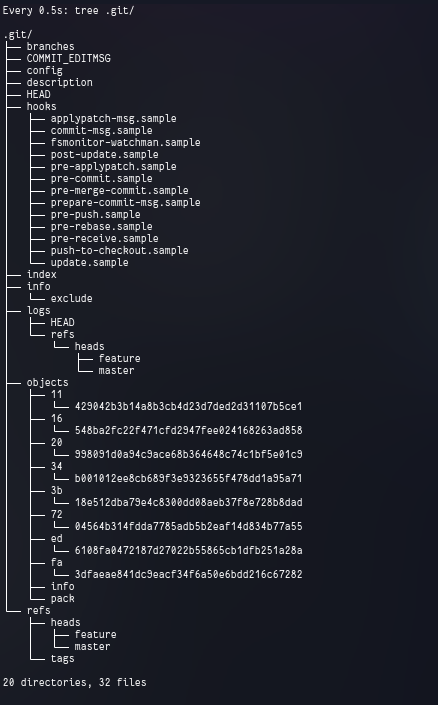

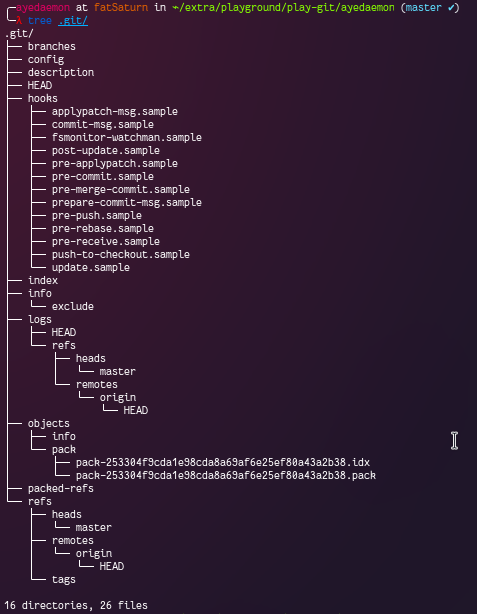

This will create a .git folder in my working repo as indicated by the output of git init command (above).

This .git folder is generally called git repository. This is the place where all of the git magic resides. All your configuration files, repo description, commit histories, information about branches, and other git related things are present here in this directory.

You can think of git as a filesystem. You add, delete, modify, tag, etc..to this filesystem and there are mainly 4 types of objects involved in the whole process - blob, tree, commit, annotated tags. (Read more about git objects)

This gives us idea that we need to monitor .git repository for changes after we run each command and understand the relation between those.

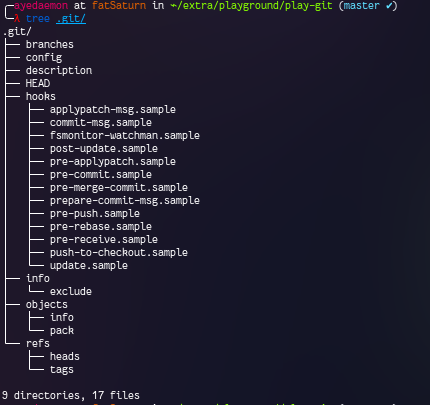

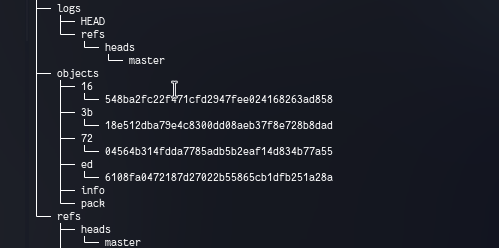

After git init this is the state of my repository. This is the initial state. So git init basically creates an initial state of this repository in the working area.

As it can be seen there are multiple hooks setting.. But they are just samples as of now. We can create our own hooks as per the need. These are simple scripts used to perform some automated tasks on some specific actions. (Read more about hooks)

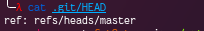

Most important thing is the HEAD. This is a file which is like a pointer to the commit we are pointing. Mostly all the changes we make are made using HEAD somehow.

HEAD points to master for now. We’ll look how this file changes it’s data with different commands we enter.

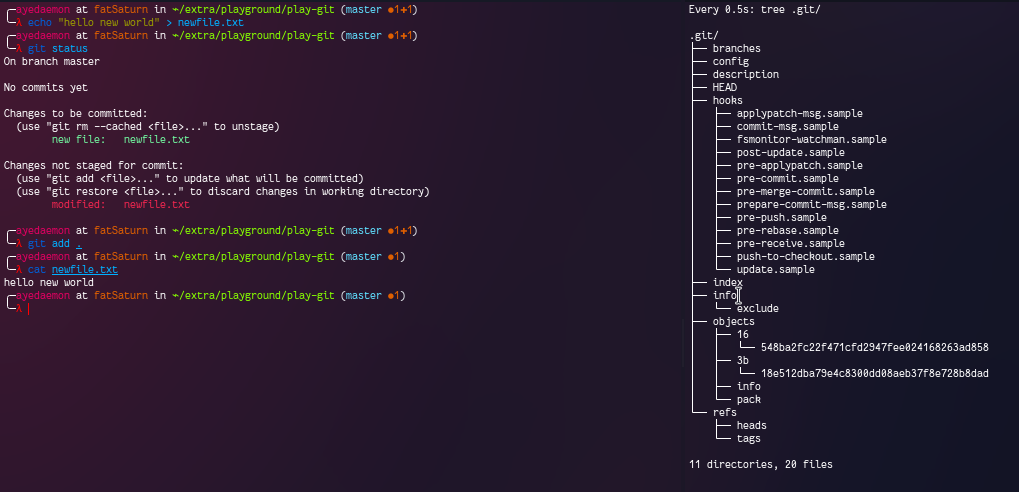

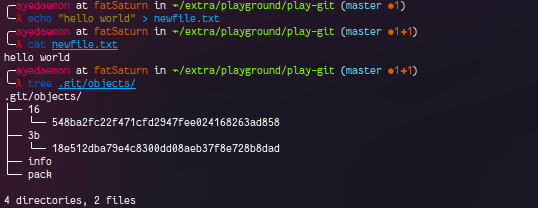

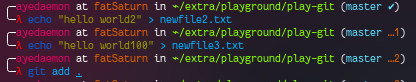

Let’s add a file and look for changes in the .git folder for each step.

Looks like there are no changes for simply creating a file and adding some data to it. But things change as soon as I git add . it. So git starts monitoring the changes as soon as I add the files using git add command.

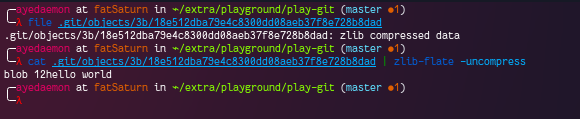

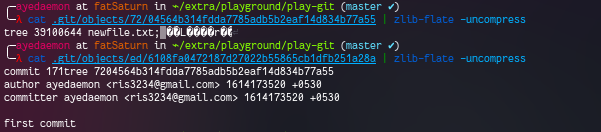

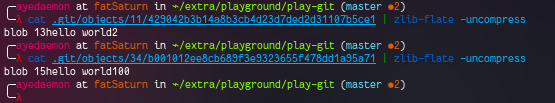

On investigating it further, we can understand that git add has created a blob object under ./.git/objects/ folder. And the file is zlib compressed data… so we can uncompress it and look at the content of that file easily using zlib-flate -uncompress command.

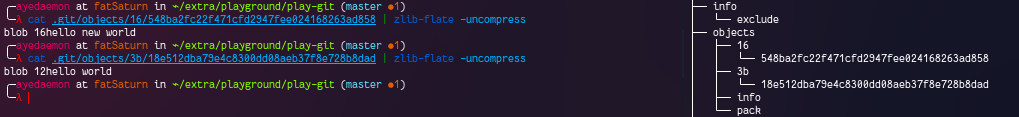

On adding a new content to the same file newfile.txt, git created a new blob object. Apparently, git does not store the diffs of the file, instead they store the complete object. So if you have 3 files with a single line of change in each of them, then git is going to store 3 different blobs, instead of storing a diff of the files.

You can also notice that here as the previous data is not yet gone from the git repository. We have both of our changes - old and new.

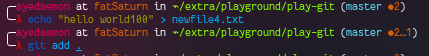

Let’s switch back again to the first data we have entered in the file.

This time they have not created any new object.. This means they create a new blob object whenever there is a new data.. and use the previous blob object whenever possible.

Now let’s see what changes do we get on commiting these blob objects.

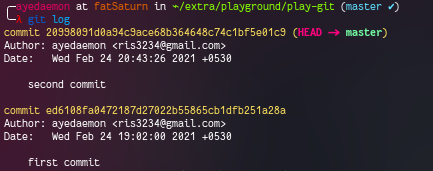

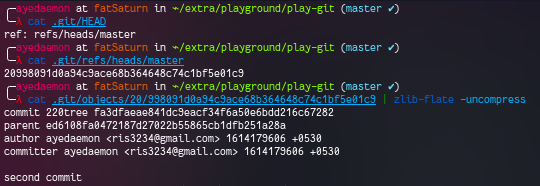

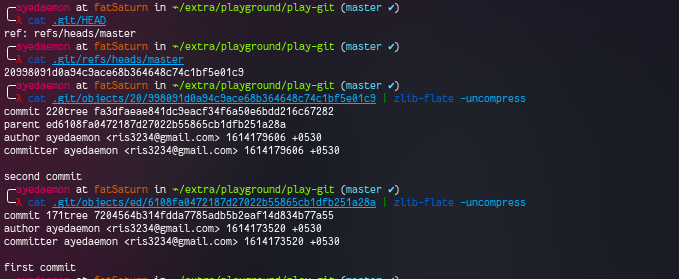

On commiting there are 2 more objects and some logs. Let’s inspect each one to see if we can get anything out of it.

One of the object is tree object and another one is the commit object. Commit object has all the information about the blob we added and the commit message along with few other details.

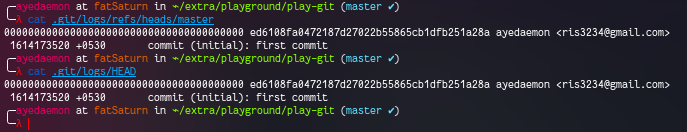

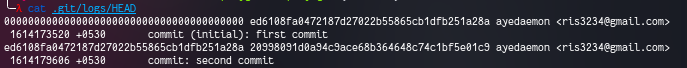

The other 2 logs which were generated are as above. By looking at these we can get that they both point to the commit object for now.

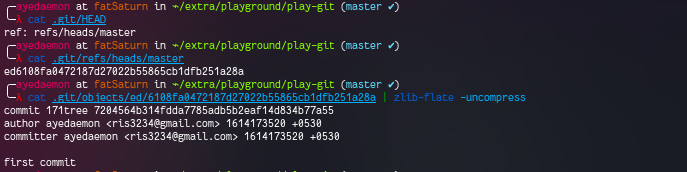

And if we look at the .git/HEAD file, it still points to this reference - ref: refs/heads/master. Further looking in .git/refs/heads/master file, we get that this points to the commit object we created.

If we are to visualize the current situation it’ll be something like this.

HEAD

+---------+

|

|

|

|

|

|

v

master +----------+

|

|

|

v

+---------+--------+

| |

| ed6108f |

| |

+------------------+

Let’s add more commits to it now.

We now have 2 new objects for 2 new files.

But if we add another file with the same content in it (In other words, if use the repeatative data) then, git will not create new blob objects for it. It’ll use the previous blob object to track it.

This means that git only tracks the data in the file along with the file name… instead of directly tracking the files.

Let’s check the logs now.

And we can get the same data from the .git/logs/HEAD file.

Again checking on the .git/HEAD

Visual diagram for the above will look something like this.

HEAD

+---------+

|

|

|

|

|

|

v

master +----------+

|

|

|

v

+------------------+ +--------+-------+

| | | |

| 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

| | | |

+------------------+ +----------------+

You can also check this from the screenshot below.

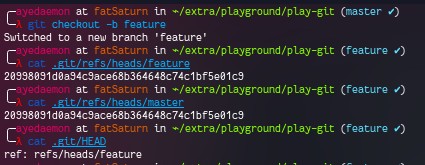

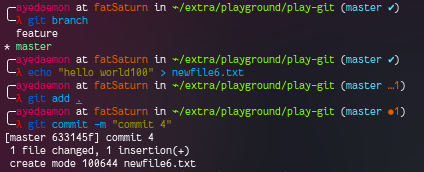

Let’s go branching now. You can create a new branch using git checkout -b feature. This command will create a branch for you. We can also observe that there are 2 new files.. 1 in the logs and another one in the refs/heads.

Let’s see what’s there in these files.

We can observe 2 interesting things here:

featureandmasterbranch point to the same commit at the moment..git/HEAD(HEAD) points to thefeaturebranch. This means whatever changes we will make it’ll be made on thefeaturebranch.

master +----------+

|

|

|

v

+------------------+ +--------+-------+

| | | |

| 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

| | | |

+------------------+ +----------------+

HEAD ^

| |

| |

| |

| |

+---------> feature +-----------+

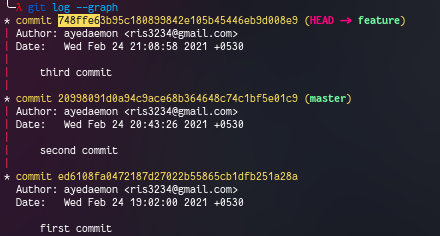

Let’s add new commits and see if we can see what we just concluded.

master +--------+

|

|

|

v

+----------------+ +-------+----------+ +----------------+

| | | | | |

| 748ffe6 +<----------+ 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

| | | | | |

+----------------+ +------------------+ +---------+------+

HEAD ^

| |

| |

| |

| |

+---------> feature +-----------+

At this point, the master is direct parent to the feature branch. So if we just merge feature to master then it’ll simply move the label one commit ahead. There is no need for a new commit to add both the changes.

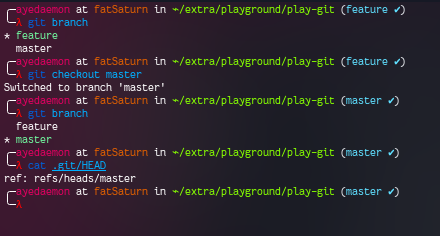

For this, we need to change back to the master branch. Behind the scenes, this will simply change the .git/HEAD reference to master from feature.

And visually, it’ll look something like this.

HEAD

+---------+

|

|

|

|

|

|

v

master +--------+

|

|

|

v

+----------------+ +-------+----------+ +----------------+

| | | | | |

| 748ffe6 +<----------+ 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

| | | | | |

+----------------+ +------------------+ +---------+------+

^

|

|

|

|

feature +-----------+

We can see that there are some changes in the feature branch that master branch does not have yet. We can merge feature branch to master branch to get these features in the master.

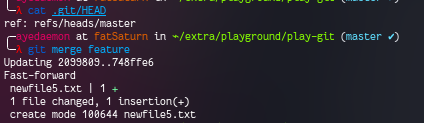

To merge, we need to switch to master branch, and then simply merge it.

This type of merge is called fast-forward merge (as given in the output). This is simply moving forward and shifting the label (master) to point to appropriate commit.

HEAD

+---------+

|

|

|

|

|

|

v

master +--------+

|

|

|

v

+----------------+ +-------+----------+ +----------------+

| | | | | |

| 748ffe6 +<----------+ 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

| | | | | |

+----------------+ +------------------+ +---------+------+

^

|

|

|

|

feature +-----------+

Let’s make more changes to feature and master both. And then merge them.

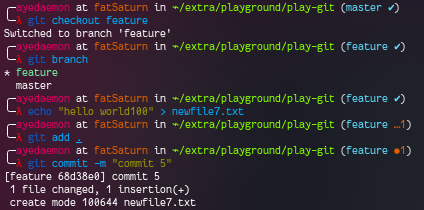

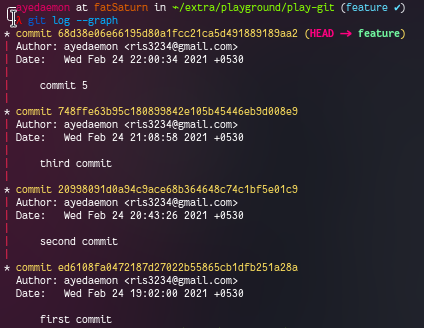

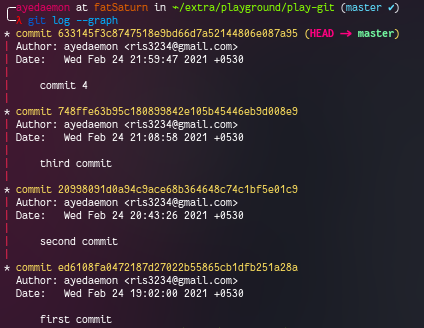

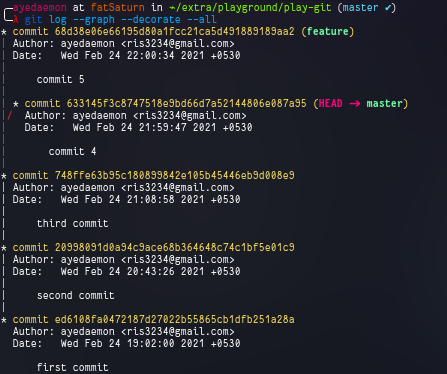

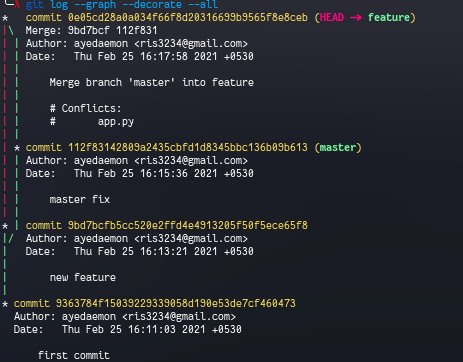

Looking the logs in feature branch, we get -

And for master branch -

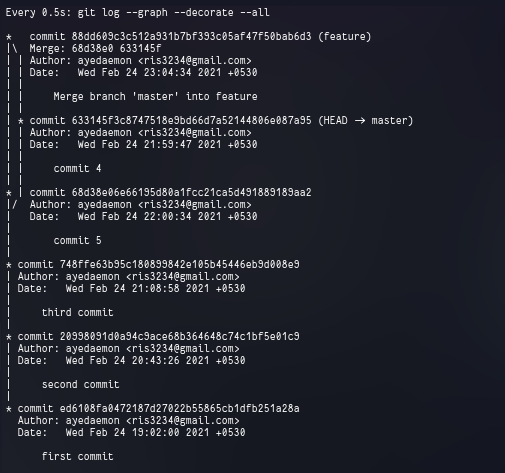

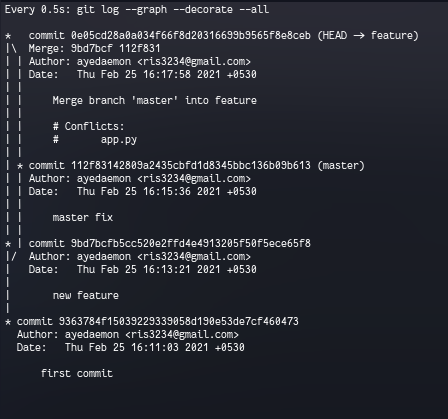

We can clearly see that both have all the commits same except the latest one. And since both the branches had their different log files they have separate logs. But we can use a pretty handy command to check both the logs combined and a graphical representation (sort of) for both.

git log --graph --decorate --all

Since I am in my main branch right now, so the HEAD points to master.

This situation will look something like this diagram below.

HEAD

+---------+

|

|

v

master +--------+

|

|

v

+-------+-------+ +----------------+ +------------------+ +----------------+

| | | | | | | |

| 633145f +<--+--+ 748ffe6 +<----------+ 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

| | | | | | | | |

+---------------+ | +----------------+ +------------------+ +----------------+

|

|

|

|

+----------------+ |

| | |

| 68d38e06 +<--+

| |

+-------+--------+

^

|

|

feature +-----------+

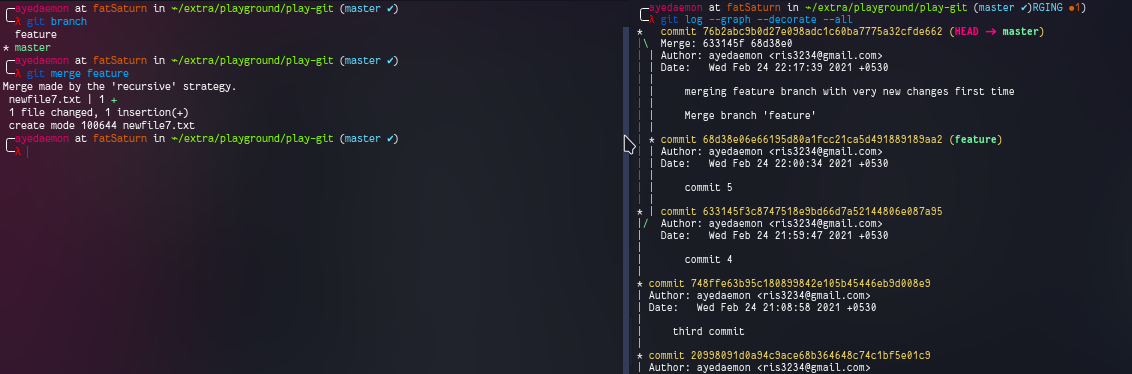

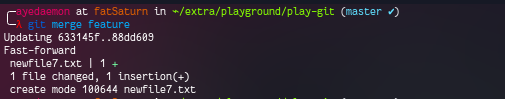

let’s see what happens when we merge these 2 branches now.

This time it creates a new commit to merge both the branches and moves label master ahead to that commit, along with the HEAD.

HEAD

+---------+

|

|

v

master +--+

|

|

|

v

+-------+---------+ +---------------+ +----------------+ +------------------+ +----------------+

| | | | | | | | | |

| 76b2abc +<--------+ 633145f +<--+--+ 748ffe6 +<----------+ 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

| | | | | | | | | | |

+-------+---------+ +---------------+ | +----------------+ +------------------+ +----------------+

^ |

| |

| |

| |

| +----------------+ |

| | | |

+------------------+ 68d38e06 +<--+

| |

+--------+-------+

^

|

|

feature +-----------+

In this merge, master calculated that it is not in the same hierarchy as feature. So it created a new object, merged the data from the feature and commited it as any other object.

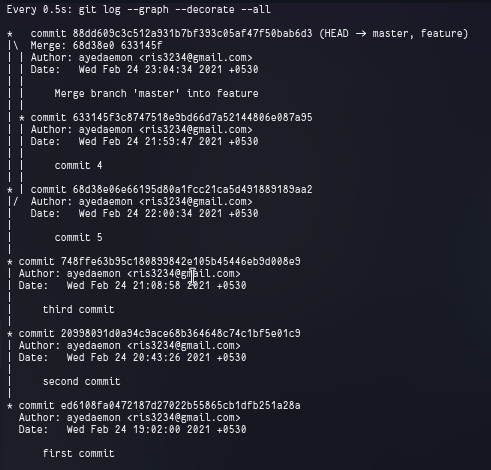

After merging, master and head labels will move forward to the latest commit. But the feature will be the same as before… as we have not changed anything in that yet.

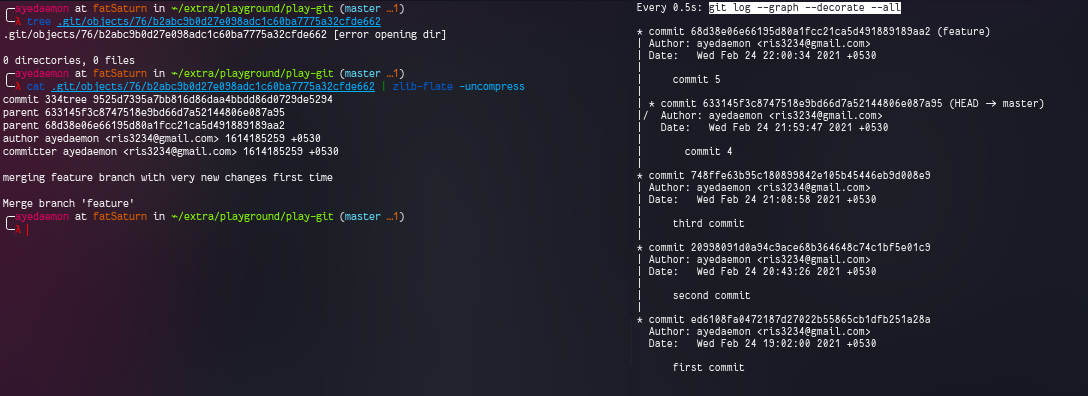

What if that this new commit 76b2abc was a mistake and we want our master and HEAD labels back to commit 633145f?

We can simply reset the commits by git reset 633145 command. This will move my labels back to this commit mentioned.

Interestingly enough, this will not remove the commit 76b2abc from the .git/objects/ directory. It’ll simply write a new log in the logs file and git log --graph --decorate --all command will give you a good output back.

What if we want to test the new feature with all the current updates of master?

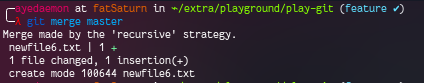

For this, we need to go to feature branch and merge master to it using git merge master

(I had to remove newfile7.txt from master branch in order to switch the branch as there were few changes untracked. There are other ways around this as well, but to keep things simple I just deleted it)

This is again recursive strategy merge.

master +--+

|

|

|

v

+--------+------+ +----------------+ +------------------+ +----------------+

| | | | | | | |

+-------------------+ 633145f +<--+--+ 748ffe6 +<----------+ 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

| | | | | | | | | |

| +---------------+ | +----------------+ +------------------+ +----------------+

| |

| |

| |

| |

+--------v--------+ +----------------+ |

| | | | |

| 88dd609c +<--------+ 68d38e06 +<--+

| | | |

+--------+--------+ +----------------+

^

|

|

+-----> feature +------+

|

|

HEAD+

This way there was no change made in the master and a new feature was added and can be tested properly. You can call this feature integration test. If the feature passes the tests and we decide to update master with this feature, we can simply switch to master branch and merge feature to it.

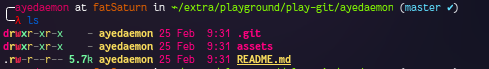

After checking out to master using git checkout master command, HEAD points to master like in the screenshot below.

On merging, we get a fast-forward merge since the master is direct parent of the commit which is to be merged and there was no need of a new commit to be created.

After merge, master, HEAD, and feature point to the same commit.

+---------------+ +----------------+ +------------------+ +----------------+

| | | | | | | |

+------------+ 633145f +<--+--+ 748ffe6 +<----------+ 20998091 +<-------------+ ed6108f |

+-----> master +--+ | | | | | | | | | |

| | | +---------------+ | +----------------+ +------------------+ +----------------+

| | | |

HEAD+ | | |

v | |

+--+------------v-+ |

| | +----------------+ |

| | | | |

| 88dd609c +<--------+ 68d38e06 +<--+

| | | |

+--------+--------+ +----------------+

^

|

|

feature +------+

Collaborating with git

Usually we don’t use git standalone in our machine. What I mean is, we do use git locally most of the time but at some point we need to share our commits to someone else via network.

To cover up the whole picture in a line –>

To **get commits** from someone else we need to do `git pull`... and to **send our commits** out on the internet we need to `git push`.

I am going the way we usually go and do things - “start with cloning a repo”. After cloning a repo I have got this.

Let’s inspect it.

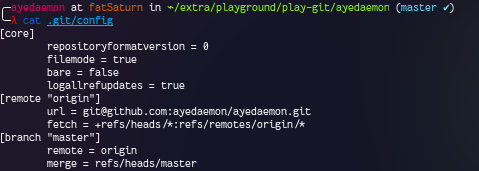

This time there are no obects like the last time. But we have new kinds of files - pack and idx. Git creates pack file(s) by reading a list of git objects and then convert this pack file to idx (index) file. This can be used by git to know the information about the git objects used to create pack file. But this is not important at the point.

The point I wanted to get started with is remotes. There is a new reference in .git/refs/ directory that points to something called remotes/origin/HEAD.

So what the heck is origin anyway? Why should I care?

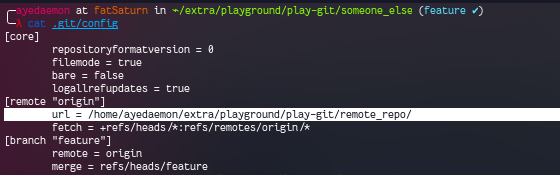

If you go out and check the .git/config file…you will know what origin means.

Here origin is just a name that points to the github repo from which I cloned my current repository. So yeah, you should care about it if you have any intensions to push/pull to this remote repository anytime in future.

Any branch with syntax like refs/remotes/*/* is called remote tracking branch. As the name suggests, it helps in tracking the remote status. It always show the remote status according to the last time both were synced together..and then they stay where ever they are until they are synced again.

So from all this, we can see that there is no exact need for origin or simply remote to be on the internet or in the network all the time. They both just need to be in contact whenever these needs to be synced. After that’s the whole point of being a distributed system.

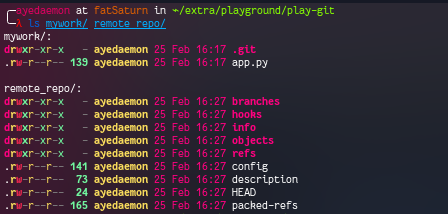

What we need is a remote repository..that can give us the pack files…and other objects… and then a working directory that we can use to add our changes and maybe another working directory that someone else is using to make his changes.

Workflow I am going to use now is as follows:-

start project

+

|

v

add new file

+------------+ +-----------+

| |

v v

make a feature fix some old bugs

+ +

| |

| |

| |

| |

v |

|

integrate and test new feature <------+

+

|

|

|

|

|

|

+---------> (Push now)

After integrating master to our feature we have:-

- a

featurebranch with new feature and base frommaster. - and

masterwhich is not changed.

So if we want we can always use the previous stable version master or the bleeding edge feature.

Now time to push it… But instead of actually pushing it, I’ll make a local bare clone that is exactly same as the repo handled by github or similar after you make a push.

To make a bare clone of the repo you can use --bare option and rest is same.

Command:- git clone --bare mywork remote_repo

Now I have 2 repos… And the remote_repo has the content of .git folder… It does not have any tracking branches this time. Well, we don’t need tracking branches in this repo. Do we?

Also I can see that all the commits I made are present there in the remote_repo.

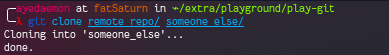

Let’s say now someone clones this repo…

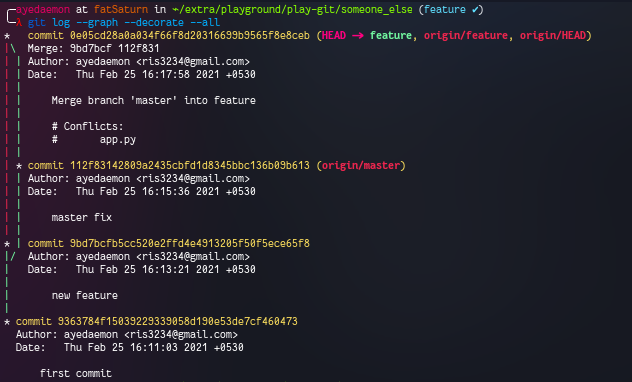

He also gets all the commits from the remote repo

With my remote_repo as the origin.

Because origin can be any bare repository.

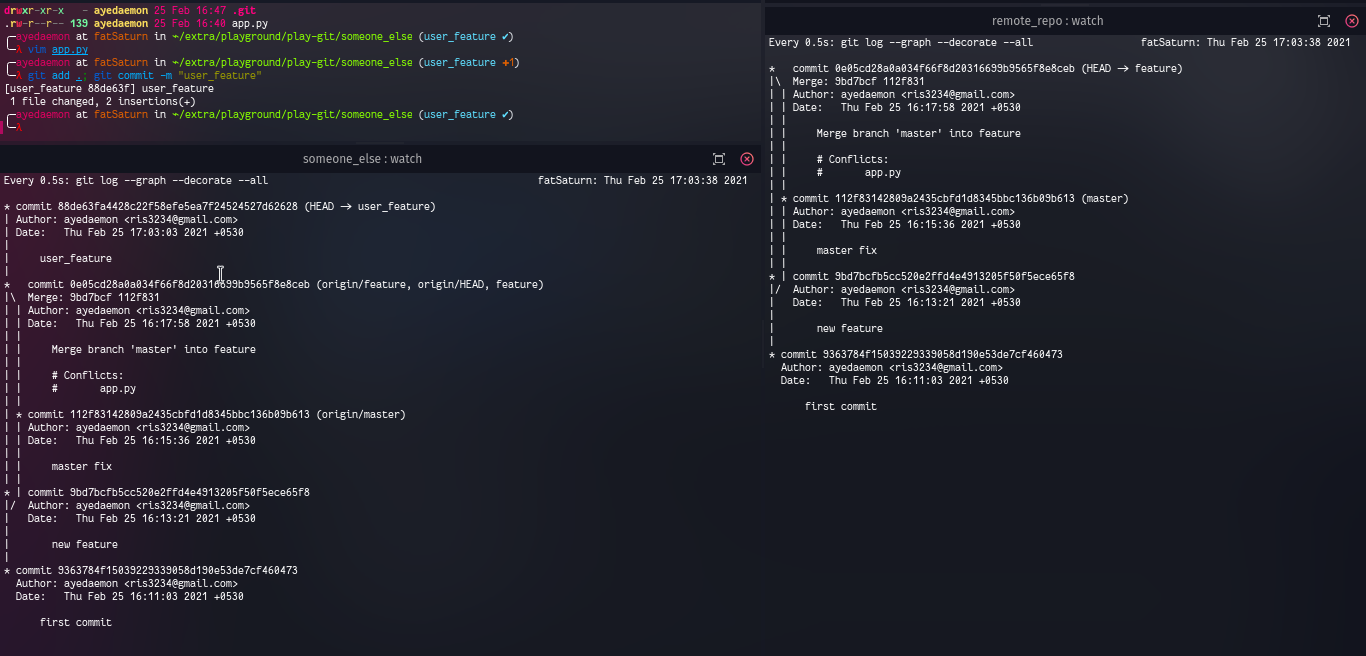

After someone has added their own branch and commited that change to his repo. Now he is ready to push/share the changes to/with origin.

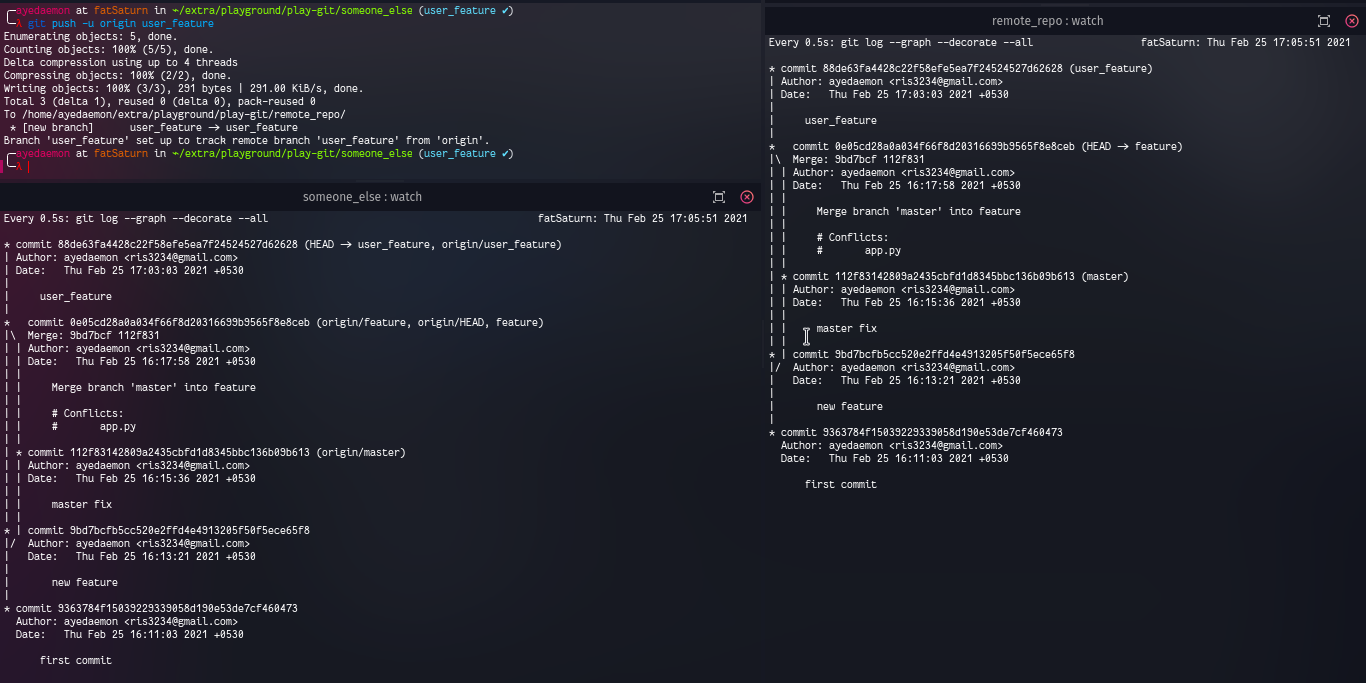

He can share the data simply using the push command.

Now our origin has got that new branch. So I had made changes to master branch it would have reflected in the master branch of the origin.

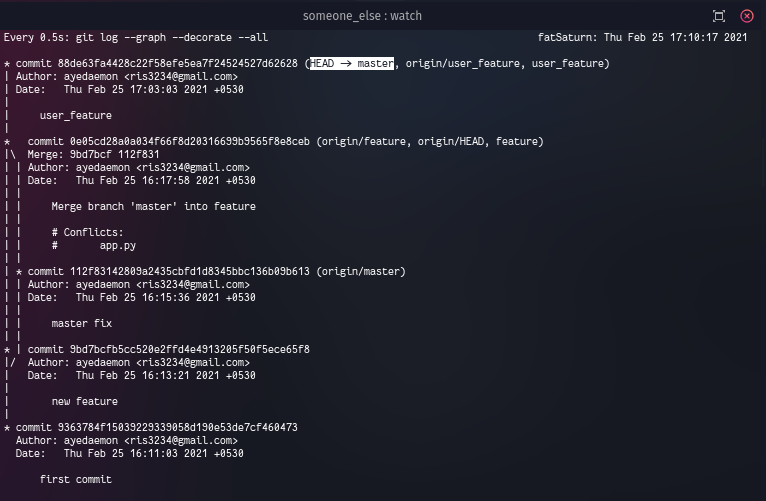

After running below commands, someone can switch to his master branch and merge his user_feature branch.

git checkout master

git merge user_feature

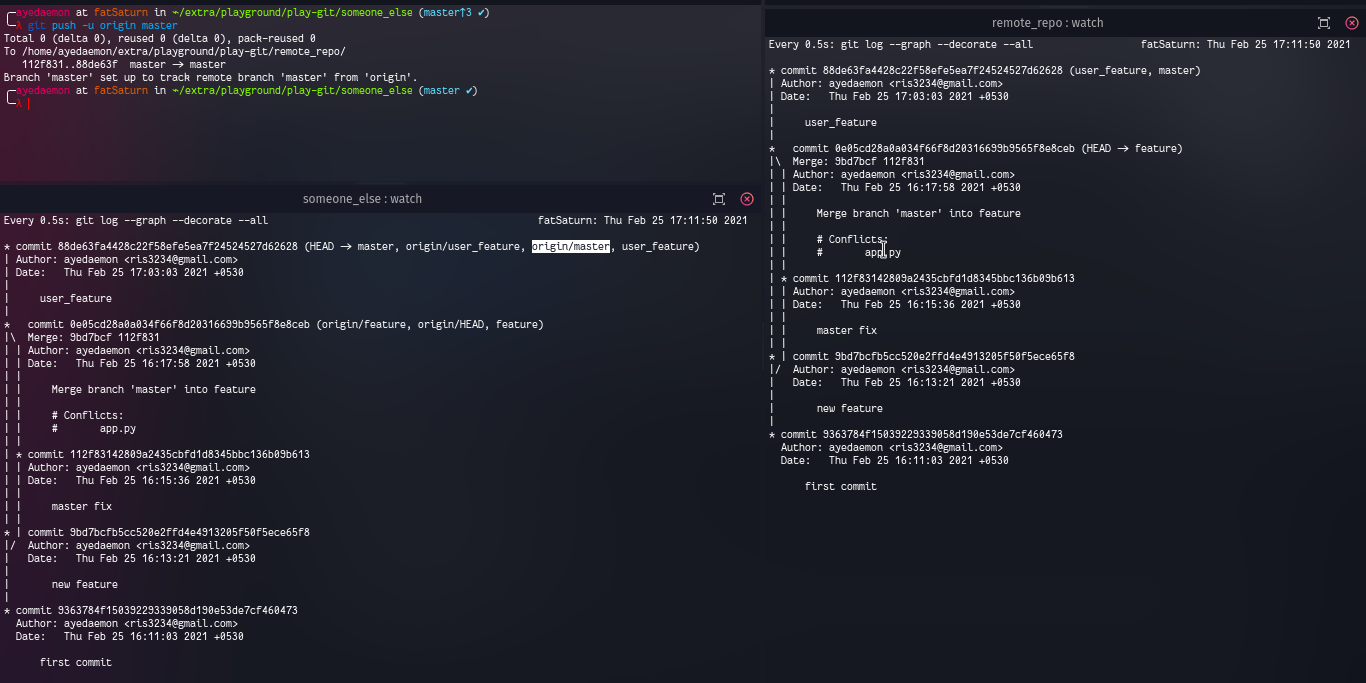

master has now got all the new commits. Time to push/share master to our origin.

After pushing changes to origin all the commits made to master are shared with origin/master and now both of them point to a single commit.

I can also pull the changes from remote_repo to mywork… the only thing I have to do is set a remote that points to the repo I want to pull data from.

Or for now I can simply specify from where to pull and merge where.

git pull ./../remote_repo/ master

This will give me the latest commits made by someone and pushed to remote.

Conclusion

This is how a typical git flow works. There are obviously other git flows better and complex than this but knowing this flow gives you a basic idea of how to make your way around git and use it effectively to manage your project.

Where to go from here??

You should start playing on your own exploring more commands and looking up their help pages for descriptions and other information. I’ll recommend to read the Pro Git Book to understand other concepts as well. It is available for free.