How your x86 program starts up in linux

In this blog, I will assume that you have basic understanding of assembly language. If not, then you should consider learning it. Although I’ll try to explain things in the easiest terms as possible.

Basic C program

Let’s start with a basic C program…

CODE: (Saving it with simple.c)

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

printf("Hello main");

return 0;

}

… and compile it the way we have always done it with gcc.

gcc simple.c -o simple.out

Now I have got a file simple.out which should be my executable binary.. I have a habit to check the file using file command to be more sure.

$ file simple.out

simple.out: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=11c9b757baf9a3a8271443682135b7488cb04e52, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

And now we know that it is an ELF binary and dynamically linked.

Let’s see what shared objects they use.

$ ldd simple.out

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fffbc364000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/libc.so.6 (0x00007f5b0d6a7000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 => /usr/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f5b0d8b9000)

The interesting one here is libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/libc.so.6 (0x00007f5b0d6a7000). This shared object is used in almost every linux command you know. On checking the man page for libc.. I came to know that it is the standard C library used in linux.

The question I am asking myself here is –> Is this somehow responsible to execute the main() function in C programs.

Maybe. We’ll see that later.

Let’s decompile our simple binary.

I can check the assembly code of the executable using objdump -d simple.out command on my terminal. It’ll give me a lot of output but right now I am concerned about the main() function… so I’ll just grep it.

$ objdump -d simple.out | grep -A12 '<main>:'

0000000000001139 <main>:

1139: 55 push %rbp

113a: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

113d: 48 8d 3d c0 0e 00 00 lea 0xec0(%rip),%rdi # 2004 <_IO_stdin_used+0x4>

1144: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

1149: e8 e2 fe ff ff callq 1030 <printf@plt>

114e: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

1153: 5d pop %rbp

1154: c3 retq

1155: 66 2e 0f 1f 84 00 00 nopw %cs:0x0(%rax,%rax,1)

115c: 00 00 00

115f: 90 nop

If you don’t understand assembly, I get what you are feeling right now

But you don’t need to understand it completely right now. You can look into some syntax and they’ll make sense in some time.

Like callq 1030 <printf@plt> - this looks like out printf() function. And we know before calling a function, you need to pass its arguments on the stack. That means the mov just above the callq statement is my string Hello main (which is the argument passed to printf())

Another Question –> Is main() really the starting point of execution??

On further looking into the objdump -d simple.out command output… I can understand that there is another function_start that calls the main() function.

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000001040 <_start>:

1040: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

1044: 31 ed xor %ebp,%ebp

1046: 49 89 d1 mov %rdx,%r9

1049: 5e pop %rsi

104a: 48 89 e2 mov %rsp,%rdx

104d: 48 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffffffffffff0,%rsp

1051: 50 push %rax

1052: 54 push %rsp

1053: 4c 8d 05 76 01 00 00 lea 0x176(%rip),%r8 # 11d0 <__libc_csu_fini>

105a: 48 8d 0d ff 00 00 00 lea 0xff(%rip),%rcx # 1160 <__libc_csu_init>

1061: 48 8d 3d d1 00 00 00 lea 0xd1(%rip),%rdi # 1139 <main>

1068: ff 15 72 2f 00 00 callq *0x2f72(%rip) # 3fe0 <__libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.2.5>

106e: f4 hlt

106f: 90 nop

It does not call the main() directly.. But it takes main() as an argument and then calls __libc_start_main (from GlibC). Along with main(), it also takes __libc_csu_fini and __libc_csu_init as an argument.

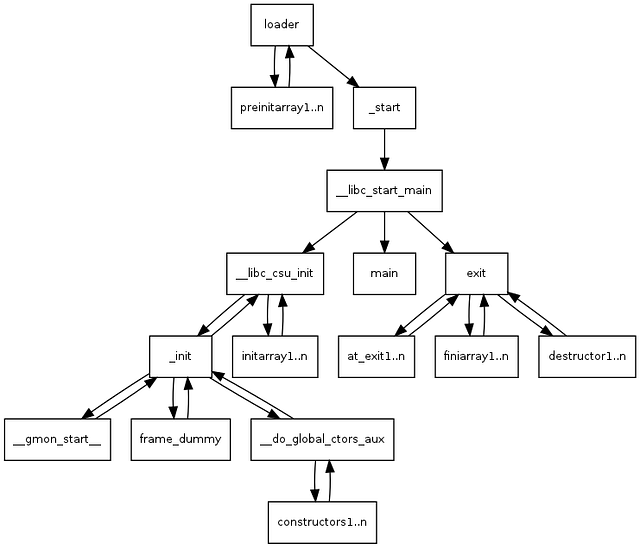

The whole picture

This image is taken from here… This is a complete in-depth blog explaining How the heck do we get to main()?

Now from the picture, it is very much clear that _start passes main (and other 2 functions) to __libc_start_main(function name was not sure from the disassembly). And __libc_start_main starts the main().

But what the hell is everything else??

To start with, Loader is a program that loads executable from disk to RAM (primary memory) for execution. In unix, it is the handler for execve() system call. As per the wikipedia page for loader(computing), It’s tasks include:

- validation (permissions, memory requirements etc.);

- copying the program image from the disk into main memory;

- copying the command-line arguments on the stack;

- initializing registers (e.g., the stack pointer);

- jumping to the program entry point (

_start).

But before getting to _start, it pre-initializes some global variables to help _start. You can create your custom preinit function as well. For this, you’ll need the constructor function. And yes, it is not C++ and it has a constructor and destructor. Every executable has a global C level constructor and destructor.

This is a code (unknown_functions.c) to change the preinit function with my own. I have added 3 printf() statements to preinit() (which should be easy to figure out in assembly now).. I’ll compile this code using gcc unknown_functions.c -o unknown_functions.out.

#include <stdio.h>

void preinit(int argc, char **argv, char **envp) {

printf("%s\n", __FUNCTION__);

printf("%d , %s , %s\n", argc, *argv, *envp);

printf("CLI arg : %s\n", argv[1]);

}

__attribute__((section(".preinit_array"))) typeof(preinit) *__preinit = preinit;

int main(int argc, char **argv, char **envp) {

printf("This is %s\n",__FUNCTION__);

printf("%d , %s , %s\n", argc, *argv, *envp);

printf("CLI arg : %s\n", argv[1]);

return 0;

}

On running it with ./unknown_functions.out, I get some expected output.

preinit

1 , ./unknown_functions.out , ALACRITTY_LOG=/tmp/Alacritty-161582.log

CLI arg : (null)

This is main

1 , ./unknown_functions.out , ALACRITTY_LOG=/tmp/Alacritty-161582.log

CLI arg : (null)

And we can also pass CLI argument to the binary like ./unknown_functions.out abcd1 and then it’ll give an output like this-

preinit

2 , ./unknown_functions.out , ALACRITTY_LOG=/tmp/Alacritty-161582.log

CLI arg : abcd1

This is main

2 , ./unknown_functions.out , ALACRITTY_LOG=/tmp/Alacritty-161582.log

CLI arg : abcd1

With this, we know that preinit function runs before main(). Let’s move forward with _start. This function is responsible to load main() by default. What if we change this function with our custom function and never call main().

I am using below code(nomain.c) and compiling it with a (special flag this time) – gcc nomain.c -nostartfiles -o nomain.out

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h> // For declaration of exit()

void _start()

{

int x = my_fun(); //calling custom main function

exit(x);

}

int my_fun() // our custom main function

{

printf("Surprise!!\n");

return 0;

}

int main()

{

printf("Not the main anymore");

return 0;

}

On running the binary ./nomain.out we get,

Surprise!!

To understand what just happened, we need to look into the disassembly of this binary. – objdump -d nomain.out

nomain.out: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .plt:

0000000000001000 <.plt>:

1000: ff 35 02 30 00 00 pushq 0x3002(%rip) # 4008 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x8>

1006: ff 25 04 30 00 00 jmpq *0x3004(%rip) # 4010 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x10>

100c: 0f 1f 40 00 nopl 0x0(%rax)

0000000000001010 <puts@plt>:

1010: ff 25 02 30 00 00 jmpq *0x3002(%rip) # 4018 <puts@GLIBC_2.2.5>

1016: 68 00 00 00 00 pushq $0x0

101b: e9 e0 ff ff ff jmpq 1000 <.plt>

0000000000001020 <printf@plt>:

1020: ff 25 fa 2f 00 00 jmpq *0x2ffa(%rip) # 4020 <printf@GLIBC_2.2.5>

1026: 68 01 00 00 00 pushq $0x1

102b: e9 d0 ff ff ff jmpq 1000 <.plt>

0000000000001030 <exit@plt>:

1030: ff 25 f2 2f 00 00 jmpq *0x2ff2(%rip) # 4028 <exit@GLIBC_2.2.5>

1036: 68 02 00 00 00 pushq $0x2

103b: e9 c0 ff ff ff jmpq 1000 <.plt>

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000001040 <_start>:

1040: 55 push %rbp

1041: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

1044: 48 83 ec 10 sub $0x10,%rsp

1048: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

104d: e8 0d 00 00 00 callq 105f <my_fun>

1052: 89 45 fc mov %eax,-0x4(%rbp)

1055: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

1058: 89 c7 mov %eax,%edi

105a: e8 d1 ff ff ff callq 1030 <exit@plt>

000000000000105f <my_fun>:

105f: 55 push %rbp

1060: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

1063: 48 8d 3d 96 0f 00 00 lea 0xf96(%rip),%rdi # 2000 <main+0xf8a>

106a: e8 a1 ff ff ff callq 1010 <puts@plt>

106f: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

1074: 5d pop %rbp

1075: c3 retq

0000000000001076 <main>:

1076: 55 push %rbp

1077: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

107a: 48 8d 3d 8a 0f 00 00 lea 0xf8a(%rip),%rdi # 200b <main+0xf95>

1081: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

1086: e8 95 ff ff ff callq 1020 <printf@plt>

108b: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

1090: 5d pop %rbp

1091: c3 retq

This is pretty small as compared to the disassembly of simple.out. The reason here is clear that we have changed the _start and not implemented any of the fancy functions in it. And this reduces the size of my binary as well.

$ du nomain.out simple.out

16 nomain.out

20 simple.out

What after _start ??

Till now, we have seen that we can pass our values to loader and replace _start with our custom functions… but this will not start __libc_start_main function.

Why do we need __libc_start_main to run??

__libc_start_main is linked into our code from glibc. In general, it takes care of -

- takes care of setuid and setguid program security problems.

- registers

initandfiniarguments. - Calls the

mainfunction and exit with the return value ofmain. (This is something that we did in our custom function -nomain.c)

This here is the definition for the __libc_start_main function which is implemented in the libc library.

As seen in the disassembly (of simple.out binary)… we can see that while calling (callq) the __libc_start_main function… we are passing main, __libc_csu_init and __libc_csu_fini… along with other things.

0000000000001040 <_start>:

1040: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

1044: 31 ed xor %ebp,%ebp

1046: 49 89 d1 mov %rdx,%r9

1049: 5e pop %rsi

104a: 48 89 e2 mov %rsp,%rdx

104d: 48 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffffffffffff0,%rsp

1051: 50 push %rax

1052: 54 push %rsp

1053: 4c 8d 05 76 01 00 00 lea 0x176(%rip),%r8 # 11d0 <__libc_csu_fini>

105a: 48 8d 0d ff 00 00 00 lea 0xff(%rip),%rcx # 1160 <__libc_csu_init>

1061: 48 8d 3d d1 00 00 00 lea 0xd1(%rip),%rdi # 1139 <main>

1068: ff 15 72 2f 00 00 callq *0x2f72(%rip) # 3fe0 <__libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.2.5>

106e: f4 hlt

106f: 90 nop

What’s next??

Next thing that executes is __libc_csu_init which will call all the initializing functions. This phase runs before the main() function. The sequence which is followed(roughly) by the __libc_csu_init function is:

__init__gmon_start__frame_dummy__do_global_ctors_auxC level global constructorsinit array

We’ll add our custom c level global constructor and init array function in below code(pre-main.c)…. and complie it with gcc pre-main.c -o pre-main.out.

#include <stdio.h>

void init(int argc, char **argv, char **envp) {

printf("%s\n", __FUNCTION__);

}

void __attribute__ ((constructor)) constructor() {

printf("%s\n", __FUNCTION__);

}

__attribute__((section(".init_array"))) typeof(init) *__init = init;

int main()

{

printf("Hello main");

return 0;

}

This will give output as below

constructor

init

Hello main

After main ??

As we have in the diagram, after main, exit function is called… which calls multiple functions in the below order:-

- at_exit

- fini_array

- constructor.

The below code(after-main.c) can be used to demonstrate that.

#include <stdio.h>

void fini() {

printf("%s\n", __FUNCTION__);

}

void __attribute__ ((destructor)) destructor() {

printf("%s\n", __FUNCTION__);

}

__attribute__((section(".fini_array"))) typeof(fini) *__fini = fini;

void do_something_at_end()

{

printf("Bye bye\n");

}

int main()

{

atexit(do_something_at_end);

printf("Hello main\n");

return 0;

}

This will return the below output - which confirms the order of execution.

Hello main

Bye bye

fini

destructor

Here we can see that the atexit function is called before the printf function but in output the atexit output is after the printf is called. The reason here is that here atexit() is simply registering do_something_at_end function to run at exit. It’s not responsible to run it right away.

The end.

This is pretty much what happens when we run an ELF binary or a C program in linux. In this article, I haven’t talked about a lot of other stuff that happens when a program executes… like setting up the environments variable for the program, how the memory layout is done or what is procedure linkage table(plt), etc…

If you find any information wrongly presented in this article, feel free to correct me. I am still learning this whole stuff and there are a lot of things yet to discover.